Credit: Australian Early Development Census (AEDC)

Since 2008, Australia has spent more than 11 billion Australian dollars over ten years to expand the government-funded nursery school (or kindergarten in Victoria) for four-year-olds to better prepare children for school.

But like our new study notes that to date, there is no rigorous evidence to suggest that this investment was justified in the first place or that it paid off.

The case of preschool financing

Almost all the policy report advocating for the expansion of early childhood education quotes the Perry Preschool Project.

This study was a randomized controlled trial in the 1960s that provided high-quality preschool education to 123 (a small sample) low-income three- and four-year-old children at risk of school failure in Michigan in the United States.

A randomized controlled trial randomly assigns participants to an experimental group that receives a treatment or intervention or control group This is not the case. Randomization balances participant characteristics between groups, so any differences in outcomes can be attributed to the study intervention.

Randomized controlled trials are considered the gold standard for policy evaluation because they provide direct causal evidence of a policy’s effectiveness.

The Perry Preschool Project found that by age five, 67% of those who participated in the program had an IQ over 90, compared to 28% in the non-program group. Nearly 80% of program group members are graduates of high school, compared to 60% in the non-program group. The program group also had better income outcomes at age 40.

While the returns to Perry are impressive, it is unclear to what extent these returns are generalizable to other contexts and populations.

Preschool in Australia

The federal government extended preschool funding for four-year-olds in 2008 improve supply early childhood services for all children. Since then, he has also billed the program as prepare better children for school.

victoria is currently deployed financed children from kindergarten to three years old under the argument that “two years is better than one”.

Recently, New South Wales and Victoria announced that government-funded preschool would expand to 30 hours a week (up from 15 now) for four-year-olds. More … than 9 billion dollars are committed over the next decade in Victoria for early childhood education, and NSW is committed $5.8 billion to extend the education of four-year-olds.

But this has not been accompanied by random evaluations of these universal programs.

A common approach to evaluating programs is to conduct a “before and after” evaluation that draws on Statistical methods. These methods compare those who chose to participate in a program with those who did not and make statistical adjustments.

This approach is second best because the methods are not designed to provide causal evidence of a program’s effectiveness.

Our study

Despite the large investment and significant increase in preschool enrollment, school readiness scores have remained stable for more than a decade.

Just over half (55%) of Australian children are on track to start school, according to the latest data Australian Census of Early Development five-year-old children entering school. In 2009, 51% of children were on track.

Being on the right track means that a child met development milestones in five important areas of early childhood development. These are:

- physical health and well-being (as motor skills and energy levels)

- social competence (getting along with other children and adults)

- emotional maturity (being nice to others, not having tantrums)

- language and cognitive skills (interested in books, recognizing numbers)

- communication skills and general knowledge (can tell a story and have knowledge for this age, such as knowing that dogs bark or that an apple is a fruit).

To better understand this issue, we conducted a population-level analysis of preschool expansion for four-year-olds on measures of child development. That is, we examined changes in school readiness as preschool/kindergarten enrollment increased.

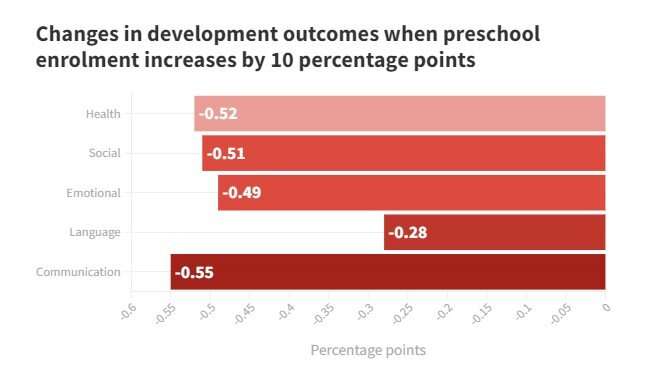

We used Australian Census data on pre-school enrollment and Australian Early Development Census data on the five developmental outcomes, and mapped these with local government areas.

The aim was to see if there are areas of evidence where preschool has developed and also improved school readiness. The analysis is not causal, but it illustrates population-level associations for children who attended and did not attend kindergarten. In addition, this takes into account the differences between regions.

Our discoveries

We found that there are no or negative effects of preschool education on children’s outcomes.

Regions that had increased preschool enrollment by ten percentage points saw their school readiness decline by half a percentage point. It involves billions being spent with no evidence that children are better prepared for school.

If we only look at areas outside of Victoria and NSW, the results are worse. The drop in school readiness doubled to a drop of one percentage point.

Of course, this analysis cannot tell how school readiness would have evolved without preschool expansion. We don’t see it. The analysis cannot say whether the children would have been less well prepared, the same or better without the investment in preschool.

What we can say is that regions that have seen an increase in preschool enrollment have not seen a corresponding increase in school readiness, which you would assume from the level of investment. Preschool expansion, as has happened in Australia, has not prepared children any better for school.

Further research is needed to determine if and how to expand preschool offerings.

More evidence needed

We are not saying that governments should not invest in children or their early education.

On the contrary. There is evidence that high quality preschools delivered on a small scale to targeted groups can have positive returns for child development.

Preschool education can have other benefits, such as more affordable childcare or labor market attachment for families. But we have found that universal preschool education, deployed for all, does not necessarily pay off for development.

Investments should be made on the basis of scientific evidence and consider how programs will be affected as they scale.

Without rigorous evidence from randomized controlled trials, money can be unintentionally spent on programs for Australian children that have no developmental effect when money could have been spent on alternative programs that give positive results.

Provided by

The conversation

This article is republished from The conversation under Creative Commons license. Read it original article.![]()

Quote: New study finds Australian preschool expansion ‘didn’t better prepare’ children for school (2022, November 16) Retrieved November 16, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-11 -australia-preschool-expansion-kids-school .html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for purposes of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.